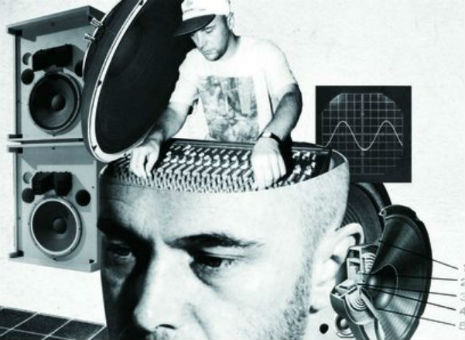

The UK Dub Master Breaks It All Down in this In-Depth Interview

Dub was born in Jamaica where the bold audio experimentation of pioneers like King Tubby’s, Augustus Pablo, and Lee “Scratch” Perry shook the foundations of recorded music. These ideas spread around the globe and took root in fertile ground, places like the UK where many Caribbean immigrants brought sound system culture with them. Dub-minded youths like Adrian Sherwood began standing outside blues dances watching the walls shake and eventually got a chance to spin a few records himself—a bit of novelty reggae with James Brown and “Funky Nassau”—progressing and learning every day as he restlessly expanded his musical horizons. He would go on to tour as mix engineer for The Clash and The Slits, and found no fewer than four labels—Carib Gems (established in 1975 when he was 17 years of age), Hit Run, 4D, and the legendary On-U Sound. His mind-blowingly mic’d, mixed and mastered recordings with in-house groups like Singers and Players, African Head Charge, New Age Steppers, Creation Rebel, Scratch, and Bim Sherman and more are the stuff of legend. And he’s still at it, having just released a critically acclaimed album in collaboration with Pinch.This conversation took place some two years ago, but it’s still every bit as current as when it happened. Like a great dub track, Sherwood moves from deceptively simple to infinite depth in a flash. Interview After The Jump…

ROB KENNER: That was a great show at the Red Bull Music Academy NYC, when you were mixing the sound for Lee “Scratch” Perry.

ADRIAN SHERWOOD: I didn’t enjoy that night. I didn’t enjoy it too much.

Why not?

It was too hot. And, a lot of, uh, drama played out as well. It was a couple of things, but it was OK. This next one’s gonna be much better though—the one that’s coming up.

The Dub Champions Festival.

Yeah. The Red Bull thing was funny. The event was OK. I thought the chat we had with Lee was quite good fun. That was quite entertaining. And the gig was alright, I was just dying under the lamps. I didn’t get it to the standard I wanted it, but it was OK. Um, but this one here I think it’s gonna be proper, so.

So is Emch gonna have some scantily clad women waving palm fronds to keep you ventilated?

Uh, better not let my girlfriend see that. I think this one’s gonna be different, you know. That one I was just on sort of a corner of a stage.

Yeah, I remember.

Under a lamp dripping for the whole show. And I didn’t have enough separation on the sound to make me as happy as I wanted. But the event itself was nice, so I think it was OK.

I’ve seen many live Scratch performances, and that was by far the best.

Oh, so that’s good to hear. That’s good to hear.

You could tell someone was doing the right things at the mixing board.

Well, I was just trying to pump you up a bit. Have a bit more attitude.

Plus you had Addis Pablo on melodica, and most of all Scratch was really feeling it.

I mean the thing with Lee is, it could be really really serious or it could be a little bit, um, a little bit cabaret. Not cabaret—just not really making the effort at times. And I think on that one, everybody involved made an effort to do their best. So I think that could be said about it. Had to push him a little bit, you know.

Yeah, yeah. Scratch was digging down deep for sure.

Yeah.

I know you’ve done quite a bit of work with Scratch, but I’d also like to ask about your own productions, which I discovered back in the late ’80s when I was working at a record shop in NYC…

Which one was that?

Irie Ites Records. I don’t know if you’re familiar with it.

I’ve heard of it. I think it does ring a bell.

It was on 7th street in the East Village.

OK, OK.

And I pretty much took all my salary in vinyl. So at the time I was taking home mostly Jammy’s 12- inches and some unusual 45s and things. But I always snapped up every “Singers and Players” album I could lay my hands on.

Good. Good.

I always enjoyed spending time inside the headphones with those. They were unlike anything else. They weren’t really dub records per se, but the dubs on there were so heavy and crisp and three-dimensional. And with all the other On-U productions I could find, you did a completely different mix for each of the different entities of the label. The African Head Charge records sound totally different than the Singers and Players records or the Tackhead records.

Well, basically I just didn’t see the point making records that were trying to copy or sound like the Jamaican stuff. I was also brought up to try and create your own sound, cause it would put you in good stead. So that’s what I always did.

You definitely did. Can you verbalize what you were trying to do with those mixes?

Well I mean my main love is obviously Jamaican music, but I’d grown up listening to things from T-Rex to… um, you know, if I go across the board, around a dozen people. I listened to [Captain Beefheart] Trout Mask Replica. The people listening to Love, the people listening to None. I had mates who were into all sorts of different stuff that I wasn’t necessarily into.

Mmm-hmm.

You take something from each thing and then it was the whole school of anti-production. I worked with the band Mark Smith and The Fall and also other non-reggae things. I was quite fascinated by the idea of making something very dry then very wet. And also hearing things like Link Wray and a lot of the really good stuff from the States. I was fascinated by the imbalance in the sound where if something was unnaturally loud and then the sound effects would be louder than the track and obviously that’s present in reggae but it’s also in a lot of great American productions where maybe the guitars are really in-your-face and the drums are small.

OK, right.

So, the idea of using dry anti-production techniques plus with the wet use of reverbs, delays and phases and distortion… I got to indulge myself by being in the studio a lot because I was paying for it myself with my little record label. And just by using certain techniques of mic-ing—which I was doing myself at the time before I became lazy—I would attempt to get a very tough harsh sound or even playing with ambience and other things. Things that weren’t necessarily in the forefront of other reggae producer’s heads.

Understood.

So I was searching very hard to get my own sound. So people would say ‘Oh well, that sounds like an Adrian Sherwood production’ or whatever. Cause I thought it would help me and it did prove to do that.

Where were you mic-ing and recording all this stuff?

Well I used to work at a studio called Berry Street Studio in the city of London. And I worked at another one called Southern Studios which was in a shed in a garden in Wood Green North London.

In a shed, really?

That’s a very interesting place because I would start at probably midnight. I’d have to wait for Crass to finish. That was where Björk started as well. She did then a band called Kukl. This was before Sugarcubes and Björk. We’d all be working the same little shed.

Alrighty then.

And there’d be bands like Minor Threat from Washington. He’d be over there. It was a lovely block. And that other producer Big Black the American lad who would come over [Steve Albini] and the Tackhead boys. We were watching his place. And obviously it’d be Lee Perry, the Hedgehog crew and Singers and Players that can breaking down the pressure in that studio. And then we’d run the entire line into the house. And we had the drum room inside that house, and then you know, every band like The Exploited and then the punk bands and all that stuff worked in that mad little studio. But it did produce some really really great records.

Were you responsible for getting everybody from Singers and Players in one place or were they doing their own thing already?

Well, the thing is, all of the things on the label were names I had. African Head Charge wasn’t a band.

Oh really? So what was it?

It was a name I had to start with where I played bass under the name of Croc. I called myself Crocodile.

OK…

Cause I had another mate called Lizard so I thought I’d call myself Crocodile. And I only ever played on a couple of records but that was the first Head Charge album. And the idea for that was basically, I know Brian Eno did My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and he made a quote saying “I have the vision of a psychedelic Africa.” And I thought, ‘Oh well that’s a bit poncy.’ And then I thought about it and thought ‘No—what a good idea.’ So I thought, “vision of a psychedelic Africa” so why not make a thing called African Head Charge and make an album called My Life in A Hole In The Ground? Cause I was working in Berry Street studios and that’s what I named the record. It eventually evolved into a band.

What about Singers and Players? How did that evolve?

Singers and Players never actually evolved into band. The idea I had for that was that they were great reggae singers and they all tended, like Johnny Clarke, to make 4, 5 albums a year. So I thought by making a kind of reggae super-group, I could have maybe, you know, like Johnny Clarke or Cornel Campbell or I Roy or whoever, come and be part of future Singers and Players projects. So I was gonna make 1 or 2 a year. But it never really got that popular. Even now, it’s a bit of a cult thing, Singers and Players. But it never really evolved like how I thought it might do.

I gotta say, that’s my favorite of all the On-U stuff…

OK, fair enough.

And where did you find Bim Sherman?

Bim Sherman. I’d worked one summer at a record shop, which was the only job I really had, at Palmer records. I heard the first ever Bim Sherman recordings coming in from Jamaica and I thought “I never heard a voice like that.” I was like a big fan.

No doubt.

So I spoke to Prince Far I and Jah Lloyd—you know, Jah Lion—and then I ended up bringing Bim to England when I was 21. I put together a tour with Prince Far I, Prince Hammer and Creation Rebel, which was another name I had that we evolved into a band.

I see.

And we did a tour called the “Roots Encounter” Tour. I was 21 at the time. So I brought Bim and stayed at my mother’s house, and he ended up staying in England until his death really. He didn’t ever go back and live in Jamaica. He set up home in England. And I helped him set up his own label, Century. I made 2 albums with him, the first I co-produced with him, an album called Across the Red Sea. That was in ’81, when I was 22, 23 and I did another one in ’93 which was called Miracle. I don’t know if you know that album?

Yes I do. It’s amazing.

I’m very proud of that I album. I co-produced that with Skip McDonald and had the percussionist Talvin Singh playing on it as well.

Yes, I remember.

That was one of two albums I produced and obviously I have been guesting on a lot of Singers and Players stuff as well.

If you were doing that at 21, you must have gotten infected with the reggae virus pretty early.

That goes back to when I was 12. So, I was running my own little disco thing at 13.

Which part of London was this?

It’s a place called High Wycombe which is probably about 45 minutes from the middle of London, going out halfway between London and Oxford.

And where did you play your disco? In the house?

No, there was a reggae club—well it was a soul club to start with—in the town. And then one hot summer it turned into a reggae club, because all the soul-fed club people didn’t come. And then the people went there with a reggae fraternity, and it turned more into a reggae club.

Me and my friends, we were too young to go in the club at 13, would stand outside while the walls were shaking. And we’d spite the owner, who’s like my father really—my dad died when I was 5—and this is a Jamaican man. He was kind of the biggest influence on my life.

I was really really slick. My friend and I started in the afternoons deejaying in the club on a Saturday, firstly and then a Sunday afternoon, doing events for 16 and younger. And then eventually after a year or two, I was playing early evenings to the older crowd before the main entertainment turned up.

Where did you get your records?

Well, I could buy them in the town I lived, off the market store selling reggae. But then I was going at 14, I was travelling to London early in the morning on a Saturday. Going to Shepherds Bush, Balham and Harlsden. I was getting some records free direct off the record companies, cause they knew me—at least Trojan and Pama. And I was buying a lot of imports coming from the States, and I’d shop for a record corner in Balham.

You were deep in at an early age.

I wasn’t just playing reggae. in the afternoons I was playing mainly pop music. You know, T-Rex, or ska records mixed with “Funky Nassau,” James Brown and all that—you know, the good hits. The kind that we liked. And then a splattering of rap, novelty reggae, and then in the evenings we would be playing a reggae set.

Was dub something you were aware of at that time?

Well certainly, dub came along when, um, probably I was 15. And only being a couple of Aquarius Dub and a couple records that come out. But the one that really got every… There were two that really were pivotal to me: King Tubby Meets the Upsetter at the Grassroots Dub.

Oh, no doubt.

And the Ital Dub by Augustus Pablo.

Right.

Which mirrored the Bob Marley album Natty Dread.

But not track for track.

No, it basically took a few tracks—what was it?—“3 O’Clock Roadblock” and all those tunes. There was a couple of remakes that he’d blown over. But the album… I remember sitting at home every night, kind of 14, 15 or whatever, playing that album with the Natty Dread album and just smoking weed at my West Indian mate’s house and then staggering back up the hill to my mother’s. And that… from that moment I basically loved the genre of instrumental or call it dub version of reggae. And I probably put out more dub albums in that period than anybody else. From when I started Carib Gems when I was 17, that was ’75 through to Hit Run and um 4D and On-U, my only labels.

“Only” four labels, starting from age 17!

I just, I had pure dub records because, arguably even all the Head Charge records are dub records. And my own solo records definitely are as well.

No doubt.

In their own way.

Yup.

Because for a lot of people internationally, they just didn’t get the DJ stuff. The DJ stuff never really sold that well. I loved it. Prince Far I, Big Youth are my heroes.

But not everybody’s ear was ready for that.

Same thing with Shabba etc.—amazing voices but… But the dub it fit perfectly. It was instrumental, set people off on a trip, and it was perfect “Smokey Bear” music.

That’s a new term for me, but I think I understand what it means.

It’s an old term in England. It was a hippies thing—Smokey Bears.

OK, so tell me about your first dub mix. How does it compare to what you do now?

Well, I had some help you see. The first dub record I put out, that I was credited as producing, I was 19. A couple of years before I met Fish Clarke. And Flabba [Roots Radics bassist Earl “Flabba” Holt] would come over with Prince Far I as The Arabs.

Seen.

And I hired Fish and a bass player in High Wycombe called Clinton Jack and I hummed all these bass lines to him and went in the recording studio with Mark, um Mark Lusardi , who um— what name did he use, what was it officially? Mark Angelo. And I got him to record it for me. And I gave it the name Creation Rebel, which is just named after a Burning Spear song.

Of course.

So then I named the band Creation Rebel and called it “Dub from Creation” & I got Dennis Bovell to mix it for me.

Oh so Blackbeard had a hand in this?

Well, he was one of my best friends. For years, from that time. He’s a genius. He’s one of the most important people in reggae music as far as I’m concerned.

Certainly in British reggae.

And I was just leaning over Dennis [Bovell]’s shoulder, like “More, more, more.” I didn’t actually mix it. I was just saying to Dennis “More, more, more…” and “Strip it down just for drama…” He was going, like, “you are mad.” We made the album in two days or something.

OK, no messin’ about.

And then the next record, actually between that one and the next one, I’d gone and done my first gigs with Prince Far I. Where I was stuck next to a fat white fellow, a nice fellow, on the mixing desk. And I said “Turn it up higher, turn up the bass.” I said “I don’t want low bass” and he said “You do it, you do it.” So I literally got thrown in at the deep end. And after four or five gigs working with a space echo and a cheap kind of spring reverb, I had it sounding absolutely wicked and people going “Oh, that’s the best I ever heard a live band.”

That’s dope.

Yeah they started really complimenting me and within a year of that, I was mixing and we were touring with The Clash, we were touring with The Slits, and, you know, some really serious gigs. And everyone was bigging up our shows. You know The Clash wrote a song—“The Bells of Prince Far I”— that’s one of the lyrics on “Clash City Rockers.” They were coming to all our gigs, as were the Sex Pistols. Everybody I could count: Lydon, Billy Idol, they were all at all all all our gigs. And then I started dubbing the shit out of it live…

Oh shit.

And getting a reputation for doing live sound. Then I then started going to the studio after. So I got my experience in the live sound in that year. And after a couple years of that, I then dedicated the next number of years to being in the studio almost nonstop.

Mmm.

And by then, I’d done my kind of apprenticeship…

I’ll say.

By understanding the, understanding the positioning of where a high hat should be in a sonic picture or where a rimshot should be cutting through your head or the foot drum through your stomach—you know, and just the depth of sound that you want to try and get live. Trying to create that vibrance in your studio work.

Is that more about the mic-ing or the mixing?

Both. I mean, I was obsessed with mic-ing. I was recording stuff then. Like um, Conny Plank you know? Playing things down tubes and remaking them and playing them through speakers in big stone toilets and remaking them off mic. And then…

In big stone toilets, really?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Then it would strike that hardness of the sound, so it was a bit of an edge and distortion. And then, listening to things like Link Wray or The Fall or other, you know, non-reggae stuff. Applying the approach of no effects whatsoever—really dry and really tough, and then maybe overload it. And then, suddenly, massive reverb and then into the delays and stripping it down. If you listen to a lot of my productions they’re very dry one minute then very wet the next. And then maybe the EQ sweeps had a kind of… You know, going to one of the great Jamaican engineers, Errol T. You know who’s doing the mixing with his stuff.

Mm—Right.

It’s quite like that. Adding bits of that and then back to a dry sound. So that all came from doing live sound where you want to hold a healthy tension in it. And that’s also present in lots of music that’s not what I was checking, which I might not have actually loved it but I loved the sonic approach on a lot of those things.

Last year I had the chance to speak with Scientist before the Dub Champions festival.

Oh yeah?

He told me that Tubby could only go so far in dub because he didn’t smoke weed. And that was the thing that helped Scientist take dub to the next level.

Yeah, but I just think that’s bollocks. I don’t agree with that at all. Well, the thing is, Scientist smokes. I don’t smoke anymore. I haven’t smoked for donkey’s years, but I remember what it’s like to be stoned. I remember what it’s like to take magic mushrooms and speed and uh, and um acid as well and other drugs. When I was younger I tried everything imaginable and I remember those visions you get. You know, the pictures and colors and what the idea of it is. I don’t think you have to be stoned to do a dub mix. I think, if I was stoned I wouldn’t really lift me to do it. Sly Dunbar and Robbie, they don’t smoke weed either.

Oh really?

Yeah, Sly and Robbie. It’s like saying you got to be stoned to make a good rhythm. I don’t think it’s true.

OK, fair enough. Which dub mixer besides yourself do you find yourself going back to the most? Who do you listen to?

I mean arguably Jimi Hendrix was doing dub, that’s Dennis Bovell’s argument.

Wow.

The first artist who stripped it down— nothing going on, then lots of things going on—was Jimi Hendrix. You know, the idea of deconstruction—taking a version, breaking down, stripping it, that is the realm of the engineer. That’s when it’s suddenly your time.

Mmm-hmm.

So you then, you know as an engineer/producer, and Scientist wasn’t really so much a producer. He was more of an engineer working on other people’s productions.

Much of the time, yes.

And he was lucky enough to be at the mixing desk of all those great Radics records.

Yes, correct.

Now at Tubby’s, you know—unlike someone like me or Dennis who’s stuck in England working our own productions and doing our own dub records—everybody would be going to Tubby’s to hear his voice and his tunes, because it was an amazing vocal place. And to get that sound that he had using that coil reverb and the couple of delays he modified.

Oh, is that how he did it?

Tubby’s had the sound. Tubby’s sound was amazing, and the volume of things that went through there alone puts him almost… It’s hard to start citing all the other great people, cause they didn’t necessarily do the volume of work that just naturally went through his business.

Right, right, right.

He could always do it with his eyes closed just by turning on his series of effects and stuff. Now if you look at other great producers of dub, I still think Keith Hudson and Brand, I think Brand is one of the best dub albums ever made. And Keith Hudson’s Rhythm Guitar Play is, uh you know immaculate. I’m a big fan of Keith’s productions and the dub records he made. I also have to say that as you go on the one who did a huge amount of work and perhaps didn’t get the credit was Errol T. You know Errol T was a absolute genius.

He did all that Joe Gibbs stuff, right?

Yeah, well it wasn’t Joe Gibbs. It was Errol T.

Right, right, right. All those African Dub Almighty albums on the Joe Gibbs label.

Joe Gibbs had his display on things.

Yes.

I’m a big fan of a lot of early Joe Gibbs, you know, before he had the studio. “Hijacked” and those tunes—amazing. What wonderful sounds. But then you’ve also got people who had their own sound. Prince Far I he had his own sound where it was the slowest one drop and more spaces than anybody. And Far I took it to the people like Bob Marley, he was one of the earliest ones in the 70s. The tours that I was part of, and others I was not part of, and not necessarily looking for any rub for myself. But Far I was out there doing it all over the place really early on, actually taking live dub out to the masses—stripped down. And those records were very good.

So what do you make of the sort of mainstreaming of dub? Dub has become almost a generic term now. Every pop record or club record has a “dub mix” and it’s kind of become a different idea now than when it was originally coming out of Jamaica.

Well, I think it’s cool. I think it’s taken years for people to get used to the sonics. If you look at the records coming out of Jamaica in the 1970–71 period, and this is then on a big sound system, it was shaking most of the outside doors. When in the States those brilliant funk records, the soul records, and I loved them but they were like clicky almost, like to dance to. So they stood up above the shag of our carpets in the clubs, you know. But the stuff coming from Jamaica, it was absolutely like, murdering people. And we just couldn’t get our heads around it. And this is what people did. And now to become so much lovers of bass…

The super-sub bass is present in everything from hip-hop to Beyoncé’s records to Britney fucking Spears and stuff—not attacking Britney Spears but you know… In production now super-sub is everything. And it came from the dancehalls of Jamaica.

I think the evolution of dub is wonderful. It’s going to jungle, dubstep, you name it—whatever. I think the top end of anything is good. You know the best end of the dubstep stuff which you know I do with Pinch, who is a great producer.

Oh yes, sure.

The reggae-flavored stuff in jungle I love. I don’t like the jazz wank stuff of… You know, fucking—I’m not naming people, but.

Yeah, who the cap fit… They know who they are.

When it became “intelligent drum and bass” and all that, it was rubbish. You know, the end of it. Where it was Rebel MC or Congo Natty, or using reggae sub cause it was really exotic, I love. I love the evolution of dub because if something doesn’t evolve, you stay in the realm of nostalgia.

Right.

And then you’re dead.

Seen.

Cause if reggae is just nostalgia, goodbye. The fact is at the moment there’s not… The sad thing for me is that there’s not brilliant new artists coming from Jamaica dealing with truths and rights and consciousness. You know, for me, there’s lots of things I would riot against. I’m not against any human beings but there’s lots of things on the planet that I’m very pissed off about.

Oh no doubt.

Things I think that are completely wrong and I would like to see some anger and some politics and some you know, “Let’s bomb the hypocrites” stuff coming out of Jamaica again. But right now that’s more likely to come out of Germany or Italy or somewhere—France or England, or the States—than it is Jamaica right now.

Have you heard Chronixx, have you heard much of him?

No doubt, yes.

Yeah he’s doing some good things in Jamaica. People like Protoje and Jesse Royal and Jah Nine and Kabaka Pyramid—there’s a few of them fighting an uphill battle.

Yeah well I think you know maybe things go through periods of whatever because of social reasons.

Yeah, true.

The last time I went to Jamaica it was kind of Vybz Kartel and whatever and it’s quite amusing, I quite enjoy it. You know, but it reminds me of when I was 13 listening to “Wet Dream” by Max Romeo or something, you know? Rude, rude, imbecilic juvenile lyrics and stuff.

Entertainment at all costs.

It’s funny, but it’s “Oh let me shoot you” and stuff. Oh God, I can’t…

There is actually more to it, but I see where you’re coming from.

You know, in this evolution of dub now we need some voices in there with the big fat burly sound systems and everything. I still think the important thing is, like Bob Marley said, the people that supposed to know the message will get it. There is a community across the world of people who are checking the consciousness, they’re checking the new productions and they are also discovering all those old great songs with the spirit of, you know, “Let’s bomb the churches and kill the hypocrites” kind of thing. You know, it’s a bit strong what I said. But…

Speaking metaphorically of course.

That kind of thing. Their ears are tuned to the new movements in dubstep or call it what you like. I personally love the stuff that’s flavored with the spirit of the early ’70s stuff. That’s in lots of good stuff that’s coming out. So what I’m trying to do, I’m working with a young producer who’s actually wicked and the record we’re making, it’s not roots reggae. But I think you’ll actually like it. There’s no point staying on same page always, I could always cut roots reggae. But right now you got to cover some young blood. That’s the bottom line I’m afraid.

For sure.

Not afraid, I mean that’s the bottom line. You’re doing this to stay and work with the thing, but embrace what’s going on as well.

Subscribe to Boomshots TV

Follow @OnUSherwood

Follow @Boomshots

EPIC. Great annotations and vids.

[…] ▶ “what doesnt evolve stays in the realm of nostalgia” – wise words from the mighty Adrian Sherwood […]