Will Sir RamJam’s Recent Soundclash On The Sea Be His Last?

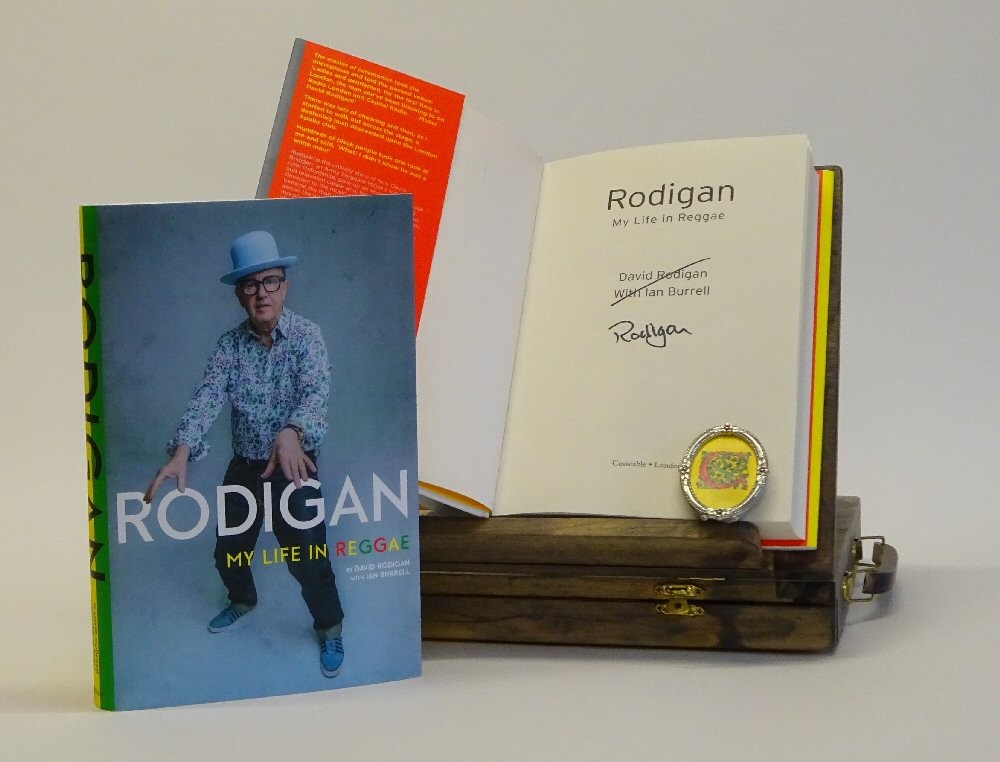

UK radio presenter David Rodigan has been described as the “outside world’s greatest ambassador of Jamaica’s musical heritage.” He’s been honored with an MBE by the Queen of England for his contributions to British broadcasting and recently published his memoirs, entitled My Life in Reggae —”the unlikely story of an Army sergeant’s son from the English countryside who has become the man who has taught the world about Reggae.” This year David Rodigan will be touring the globe once more to celebrate his 40th year in the business. He’s cut countless dubplates and won many clashes in his time, but had largely “walked away from clashing” prior to his participation in the recent Soundclash on the Sea during the 2017 Welcome To Jamrock Reggae Cruise. In this exclusive interview, Rodigan speaks to Boomshots about the roots of sound system culture, explains the difference between dub plates and specials, shares his thoughts on the true role of selectors and DJs within the reggae industry, reflects on whether modern clash culture has “spun out of control,” and speaks frankly about where he thinks the music that now inspires so much of the mainstream is heading. Interview After The Jump…

Reshma B: Everyone’s going to be excited to see you return to the Jamrock Cruise this year. I remember you played on the first cruise, and I know it’s going to be a big thing to get Rodigan back on the boat. Have you been keeping up with what’s going on?

David Rodigan: To be honest, I haven’t. No.

Since that first year, they’ve actually started a Soundclash at Sea, which you’re going to be competing in this year. The Soundclash at Sea has become quite a big attraction on the cruise. I think the lineup this year is quite exciting: yourself, Tony Matterhorn, the 2017 World Clash Winner [King Turbo], and Mighty Crown. Have you been hearing about the past clashes?

Yeah, I’ve heard that Mighty Crown’s won them all.

They’ve been doing really well and you’re obviously going to be up against them. You’ve done many clashes in your career, of course. How do you feel about this one?

Well, like all the others, it has to be fun. If it’s not fun, it’s just a bore. There’s nothing worse than a boring evening, so I’m going to have fun. I’m coming to entertain the audience.

“I never really worry about who’s going to win a clash. What I worry about is who’s going to entertain the crowd.”

I’ve seen sound systems lose clashes for a number of reasons. It can be home turf supporting another sound. It can all spin on one song. I’ve seen one song win a clash and in fact, I’ve seen Mighty Crown back in the day not win clashes—although I thought they’d actually played better than anybody else. It’s a peculiar business.

Getting back to my point, it’s all a question of what do you bring to the game? What’s your contribution to the night? For there to be a winner, there have to be competitors. Everyone has a role to play, and at the end of the game, someone wins. If there’s no competitors, there’s no game. I’m a competitor. It would be good to win, but I don’t go to events with this burning desire to win, because I think that can eat you up. I think it can become obsessive.

Music brings joy and happiness. It shouldn’t bring an excessive need to win everything. I think it was Capleton who said, “Music is a mission, not a competition,” on one of his records. Although clash culture, of course, is by its very nature about winning. But if we trace it back to its origins, it was nothing to do with having customized dubs and all that business. It was just about playing a better selection.

I think we’ve given too much emphasis to dub plates with our names in it and customized dubs. I think that hand has been overplayed in the business. It’s become—how can I say this?—it’s not really a question of how many customized or how many dubs you have with your name in it. It’s question of what do you choose to play at the particular moment in time in terms of how it can affect the night. I think that if we remember—if I spin it back—I go back a long way in terms of my memories of clashing.

“In the early days of clashing, we didn’t even have our names in dub plates. That didn’t exist.”

All you had was an exclusive recording that no one else had, because you’d go to King Tubby’s studio. You’d go to Sylvan Morris, Harry J’s studio. You would get a different mix, a four-track mix, of the song that you liked. That song then became your dub.

A “dub” technically is a copy of something that’s already been made. What you do in the traditional dub is you get a different mix of a particular recording.

“The dubs that Jammy’s mixed for me or Tubby’s mixed for me—they would mix them from the four-track. What I would then have is a very special one-off recording that couldn’t be replicated in any shape or form.”

I find with a number of dub plates now that it’s almost like “press auto-play.” You hear the same dubs from many different sound systems. They’ve all got the same dubs in many cases. One of the reasons I’ve always liked Mighty Crown’s work is that Mighty Crown are very clever at crafting alternative dub plates. I’ve always held Mighty Crown in high esteem because I think they have generated a lot of interest in clash culture.

I’m also a big fan of Tony Matterhorn—not because I’m clashing with him, but simply because he’s a masterful selector who knows how to entertain an audience. Rightly, he’s not that bothered. You can see that on his face when he’s playing. He comes to have fun, and he comes to win, of course. But with Tony, you can see him going for the crowd, working the crowd.

That’s important, and I think… Well, I don’t think, I know that’s why I got into sound clash culture: because it should be fun. When it gets too personal and when the language becomes obscene and foul, I just feel sickened by it. I find it actually rather depressing that grown adults can reduce themselves to a slanging match on stage using pretty foul language that you wouldn’t hear anywhere beyond a rum bar.

“To be honest, that’s why I’ve stopped clashing. For many years, I was so sickened by the way that selectors were behaving towards each other, I actually stopped clashing.”

It was Chin who persuaded me to come back. He said, “You can’t change something from the outside. You’ve got to be in it to change it.” That’s just the way I am. That’s my nature. I didn’t come into this business as a clash selector. I came into this business as a radio presenter who cared about the music. All selectors care about the music. That’s why they play it.

Let’s face it: you probably could be having more fun out there on the dance floor rather than spending the evening choosing the next record to play. But if you get a calling—without sounding too rich—if you get a feeling that you can do something and do it well, you kind of pursue it. Then, when you see the crowd responding to what you’re doing, that’s interesting.

“You can give the same box of records to three selectors, four selectors. Every box is the same. Those four selectors will give you a completely different interpretation of those songs in a 45-minute set.”

Let’s say if you gave 20 records to four selectors to play in one hour, you would get a completely different feeling from each selector. That’s the essence of what we do. That’s why people support individual sounds or they come to listen to particular selectors, because they like the way in which that selector plays.

I have to say, the other thing I find incredibly irritating about sound clash culture to the point where I just want to scream sometimes is this relentless talking all over the music.

“Not allowing the music to breathe. Jacking the music up after 20 seconds or 30 seconds. It just becomes like someone hitting you over the head with a hammer. What is the point of this?”

This is one of the reasons why I’ve really kind of walked away from clashing, to be honest with you. Because I just do not see the point of going up there, preparing all these dubs or sequencing a song for two or three minutes, and the selector plays the song for 30 seconds, then starts screaming all over the vocal. I’m utterly befuddled by that. I just don’t see the point. Yet, it seems to have an affect with the audience. I might just be a load of crap on the night, because I’m not going to be playing songs for 10 seconds, that’s for sure.

It does seem really odd that people would go to all this effort to get a record that’s so exclusive and then nobody can listen to it for long enough to really appreciate it. You end up listening to the selector more than to the music. That’s my criticism of sound clash culture in recent years. That’s why I’ve just walked away from it. I’m not saying you should play the song for its full duration, because equally that could be…

Boring.

Tiresome, but I think there’s a balance that could be found and should be found in terms of allowing the audience to appreciate the music that’s recorded by the singers. It’s not the selectors making these records. We’re not making anything.

“What we must never forget is that selectors are not as important as they think they are. Selectors are the end of the food chain. If there’s no recording engineer, if there’s no singer, if there’s no songwriter, if there’s no musical arranger, there’s no song.”

If we don’t have songs, we don’t have work. Selectors are the last in the food chain, and selectors need to remember that they’re there as a result of a privilege given to them. They may have worked hard for it, but it is a privilege, and they must never consider themselves to be more important than the people who actually make the music. I think that’s been another problem with selectors who have developed almost…

A star quality.

Yeah. There’s no need to make any further comment. I never forget, as a selector, that I’m playing a position, so to speak. If you’re using a football analogy, I’m playing according to my position. We must never forget that without the musicians, without the recording engineers, without the songwriters, without the players of instruments and the singers, we are nothing. Nothing!

It’s interesting that when you first started, selectors did not have their names called out in the dub plates. The musicians were always the stars. When did that change? At this point everybody sees having names called out as a staple of getting a dub plate. Some selectors definitely seem to have a certain star quality about them. They seem to feel they are completely on a level with most artists, if not even more famous…

Right. In my opinion no DJ on this planet comes anywhere near an artist. A DJ is just a DJ. We just play records. We can’t sing. We can’t rhyme. We can’t make rhythms necessarily. I’m talking about traditional DJs. You have DJs who are regarded now as artists because they make music. That’s different—but the traditional description of a DJ was a disc jockey, someone who rode a rhythm by playing it on a turntable. In the traditional description of a disc jockey, I don’t think we are anywhere near as important as the people who make the music. We merely are conduits to the audience. That’s what we do. On the radio, in clubs, we connect. We are the connecting rod which allows the public to hear the music. That’s all we do.

That is not in any way associating myself with DJs who make music because they are artists and they create music, and that’s quite different. When it changed was in the mid ’80s, when you would go to dances in Jamaica and you would hear artists singing live and sound systems such as Stone Love started introducing the idea of having a popular record cut on a dub plate, actually voiced by the artist. You’d have a hit record, and as opposed to getting a different mix of it, you’d get the artist to voice the song naming the sound system. Therefore it became almost like having a guest appearance by an artist in your set. They were referred to as “specials” because in those days, they were special.

I know that some selectors such as Bill Cosby from Stone Love pride themselves on not playing any specials in a set. I’ve seen Billy Slaughter play a set where he hardly touched a special. I think sometimes even myself, I’ve been guilty of this, of feeling that it’s necessary to play specials too much. I think we can, as selectors, get a twisted view of it.

“Generally speaking, the audience aren’t remotely interested whether it’s a special or not, as long as the record is good. It’s only the hardcore sound clash fanatics, what I call the dancehall police, who will be sitting there ticking off how many dub plates you’ve got.”

This is an inner circle of fanatics, people who are obsessive about the music. Of course, without them, it wouldn’t be as much fun. They are an important part of the game, but they are not the mass audience. The mass audience is the mass audience. I think this is important, to note the difference: the people who are absolute passionate fans of sound clash culture and the general public who like to come to a dance to listen to records. If you go to Weddy Weddy on a Wednesday night, half the general audience don’t give two hoots about whether Stone Love are playing a dub plate or a regular record because they’ve come out to be entertained—and Stone Love have been entertaining people for years, as have all the other great sounds: Bodyguard, Bass Odyssey, and so on and so forth.

I think what happened in the ‘80s was that they made this slow transition into having their names in records or dub plates. Then it sort of spiraled from there. Originally, the only thing you might get was your name dropped at the intro so they could say, “This can only be played by so and so.” Somebody might voice that for you at the studio as the engineer is mixing the dub, but generally speaking, that didn’t happen either. In England, on the night of the dance between big sound systems, you would hear the selector saying, “This can only be played by Fatman Hi Fi”… “This can only be played by Lord David” and so on. You knew when the DJ said that, what you were about to hear was a different mix. That’s really where dub plates came from. That’s the tradition behind them.

You mentioned that even you yourself might have sometimes played too many specials. But when a DJ hears their name in something they’re playing for a mass audience, it must make you feel good when you hear that.

I’m going to cut you there, because I remember some of my first specials, I didn’t even have the courage to play them. I was too embarrassed.

Were you?

I remember the first dubs I were given were dubs by Mikey Dread—dubs by Jah Walton. I don’t know if he was known then. He’s now known as Joseph Cotton. This was in ’81, ’82, very early ’83, around that period. I was given acetates with my name in them. I couldn’t play them in public. I was too embarrassed.

Just because you felt like you were not at the level of an artist?

No, no. Nothing to do with that. Because, people would say, “Who the hell do you think you are? Playing a record with your name in it?”

It seemed too arrogant?

Arrogant. Absolutely, yeah. It was arrogant and full of pomp and pride to do that. I couldn’t do it, because it didn’t exist in those days. It really didn’t exist.

How did you get over that? Just because it became a normal thing?

What happened was I realized that in order to continue this clash thing, you had to cut more of these songs with your name in them. One of the biggest clashes I did outside of England was in ’93 against Waggy T, who’s an amazing selector. I really, really rate him as one of the true great selectors ever, because no one can mix like him in my opinion. He’s an amazing mixer and one of his greatest qualities was the fact that he never, ever spoke. He allowed his music to speak, but he didn’t get in the way of the music. He allowed the music to breathe and he allowed it to play.

When I first played with him, I clashed with him, and he had an MC. But, that night was the only night the public had ever heard him speak. He spoke a couple of sentences in response to a comment I had made, and that was the only thing he said all night. The point was that I realized in that clash that I needed to get more recordings with my name in it. Because what was happening was you were being challenged… The clash demanded of you that you dubs with your name in them, and then these rules were introduced where the “45 shop was locked.” Therefore, you could only play dubs after the second round. That was another reason why the game spiraled into this.

Don’t get me wrong—I understand it, and I think it’s very exciting in many ways because it brought out the best in many selectors to come up with original ideas about dub plates.

“What I found infuriating was that you’d find an original idea for a dub. You’d write some lyrics. Then, two months later, three months later, ten sound systems have copied your dub.”

But that was inevitable, I guess. In the early years, everything was new. I was the first person to voice Gregory on some of the recordings that I put in, in terms of dubs that I got recorded. I wrote the lyrics, and he never voiced those songs before.

Of course, I’m not saying that I did this first. Please don’t misquote me on that. I’m just saying that in certain cases, with certain songs, I knew that I was the first to get them, because those were the early years of dub plate cutting. I think dub plate cutting now has reached a point where… Actually, it’s ridiculous. What I find objectionable, highly objectionable, is when artists choose to counteract customized dubs. I think that is utterly sickening and completely out of order.

For an artist to voice a customized dub for a particular clash in favor of one sound and naming the other competitors as losers, in effect, then to go to another selector and voice a customized naming the person who he’s just voiced for as a loser is despicable. I don’t know why on earth an artist would reduce themselves to that. Are they that desperate for money?

I’ve seen that in clashes in recent times where a selector proudly plays a customized dub by an artist that supposedly can only be played that night. Then, the next minute, the other sound system is playing a customized from the same artist counteracting it. That’s not a counteraction. That’s a mugging. You just got mugged off by the artist. Thanks. I’ll take your money. You’re the mugs. See you!

Does that mean you will not be having any dubs cut especially for the clash on the cruise?

I doubt it. I doubt it very much. What’s the point? You think I’m going to spend the next four weeks customizing dubs to be played for 30 seconds?

And only to be played on that night.

Do you think my life’s that dull?

Well, as you said, it’s ridiculous to think that they could only be played for 30 seconds at that specific place and time—only to hear that same artist who’s taken your money take somebody else’s money to counteract your dub. What you say is absolutely true. I’ve been to many recent clashes were this is happening. It doesn’t make sense for the DJ, especially. The audience might enjoy it for that moment, but it doesn’t make sense for clash culture as a whole.

Well, I think it’s absurd. I think it decimates the whole purpose of taking the time and trouble to approach an artist, pay an artist, spend time getting that done. All this takes time. I’m not full time clash sound system. I’m a full time broadcaster. I spend most of my time broadcasting, working at the BBC. I’m on Radio One. I’m on Radio 1Xtra. And, I’m on Radio Two. My prime concern is radio, and it always has been. In 2018 I celebrate 40 years as a broadcaster. Clashing was only ever for fun. It was only ever a sport in the way that you would play tennis or badminton or have a game of soccer. I never became obsessed with it in a full-time way of living for the next clash.

“Although I have clashed a few times over the years, if you look at my list of clashes next to others, you’ll see that it’s not something that I’ve been terribly obsessed with. It’s something that I’ve done to have fun.”

The whole idea of spending several weeks or months running down artists to voice songs that can only be played once in one night naming your competitors is fine if you’ve got the time and the money to do that. Go ahead. With all due respect, I guess if you’re a full time sound system and there’s three or four of you and you’re playing out three or four nights a week, and you’re traveling the world, then maybe you think that’s necessary. I’m not saying I won’t cut a customized or two, but I’m certainly not going to be coming to the clash armed with customized that are going to be played one after the other. I don’t see the point of that. I just don’t see the point.

What I see the point of it is to play songs that are pertinent in either a story-telling sequence or by way of sharing things that are important. This music is very, very important. It’s a powerful music. It is a music that speaks out for people, for humanity. Primarily, the reason this music became so popular was because of its social significance and poignancy. I’m not going to start listing the songs that we all know and revere, but there are many.

“Sound clash culture is, with all due respect, an element of the music—but it is not the most important part. The most important part of the music is the music itself.”

Like anything in life, people do like competition, whether it’s a football match or a boxing match. There’s an element of sport in sound clash culture. I think it must always be fun. It must never be derogatory. It must never be humiliating. I think it’s important that those guidelines are maintained and that discipline is exercised.

Congratulations, by the way, on the 40 years. That’s an amazing feat for anyone in any genre. You mentioned you’re not going to come armed with custom dub plates. Every DJ’s going to have their own thing. Just in a nutshell, what can the audience expect from Rodigan?

Good music.

“I’ve got hundreds of dub plates, hundreds, and I could only touch the tip of the iceberg. One of my problems as a selector is that I’ve got some seriously deep dubs. If I don’t have the right audience, they go over the heads of the audience.”

I was going to ask about that. After forty years your music box must be pretty large.

I’m a record collector. I’m sitting here in a library. I’ve collected records all my life. I now have very, very specific dubs that relate to different periods in time. One of the problems I have is that I have to be mindful that when you’re playing to an audience, they may not get it. I’ve got dubs, and I think all selectors have got dubs, that mean something to them. But they don’t necessarily translate to a mass audience who probably won’t even know the name of the rhythm, never mind the name of the artist or the song.

There’s no shortage of dub plates where David Rodigan’s concerned. Be quite clear about that. But what I have no intention of doing is coming to play with load and loads and loads of customized. If someone wants to play a bunch of customized dubs only, please go ahead. I’d love to hear them. I don’t need to call someone’s name in a dub in order for that dub to impact upon them.

When did customized dubs become such a popular thing?

In the early days of clashing, there were hardly any customized dubs. There might be a little sketch or something. I was one of the first people to introduce characters where I’d come on dressed as someone with a punchline or a sketch. I brought humor to these clashes, acting out scenarios about who I’m competing with. That’s something I did, and I know I was one of the first people to do that. Then, I had sound systems approaching me to write skits for them. So there’s an element of that. But I actually don’t need to name another sound system in order for a dub to impact upon them.

I think that’s where this business has spiraled out of control. Because, what it’s done is it’s imposed a tremendously heavy burden on selectors who simply don’t have the money to do this. Large amounts of money are being used in order to cut these dubs. These young sound systems, they simply don’t have the finance. That’s why I admire what Irish and Chin are doing by giving these young sounds an opportunity to come through. It’s mind-bogglingly expensive for sound systems to voice loads and loads of dubs. It’s not practical.

Many young sound systems that I know, they pool their money. They pool some of their own wages, never mind their own gig money, in order to voice a couple of specials occasionally. There was a time when the recording of specials was relatively inexpensive. Sometimes they were given as gifts to selectors by artists because they wanted their songs to be promoted.

“With certain artists, dub plate cutting has become quite expensive.

I get that too, because artists need to live and frankly artists are not really getting money from record sales because there are no record sales anymore. They’re dependent upon touring and voicing dubs.”

My heart goes out to the artists, because the industry has been decimated by the lack of vinyl and so on. Because of the way it’s changed. My heart goes out to artists who are even more dependent upon touring in order to earn a living. Remember these are the people that enable us as DJs to have fun, because these artists are writing songs and taking the time to record songs.

You have to ask yourself, who’s actually buying these songs? Are they selling on iTunes? If they are selling on iTunes, how many are they selling? That’s why I salute artists, because they’re still putting their shoulder to the wheel recording new songs. In the old days, they could actually earn something from them. Nowadays I have to ask myself how?

I think they do it for a passion. They do it because they have to do it, because when they started out in this business in the ’50s and the ’60s, no one was doing it to earn money. They were doing it because they had to do it, because they wanted to do it, because it was fun. Remember, this is an art form. People don’t become artists to earn money. They become artists because they want to do it so much. They want to sing. They want to dance. They want to paint. Because they have an artistic persuasion. They don’t do it to earn money. They just don’t. They never did. If we put money first, then it’s over. We’re doing it for the wrong reason.

“I send a message to all young sound systems: please, please, please, don’t concern yourselves with how many dub plates you’ve got. Don’t concern yourselves with breaking the bank by trying to voice everything you possibly can.”

Not every dub plate can be played. Not every dub plate will be as good as the 45. You don’t need to play dub plates all night in order to entertain an audience.

So, how do you make your name as a sound system?

Stay true to yourself. Stay true to the music.

Changing gears a bit, how do you feel about things like the Red Bull Culture Clash? I just recently went to Atlanta this summer where they were holding their annual event. They are actually taking Jamaican culture and turning it into something else. I’ve heard about some extraordinary amounts of money being used for each sound system to collect dubs there.

That’s a different world. That’s a world that’s governed by a major international conglomerate called Red Bull who put their money into many different things. Into sport, that space mission, all sorts of things. They’ve chosen to use the profits from the business in that way. They are paying big artists to take part in clash culture. What they’re doing is they’re taking the essence of what we know to be clashing, and then they’re spinning it on its head. They’re saying, “Actually, it’s not about everyone playing the same type of music all night. It’s about people playing different types of cultural music from drum and bass to hip hop to house and so on—and reggae.”

So, they’ve taken the format, and they’ve given it a different feel. If anything, what it’s done is it’s led people to understand what clash culture is. If people are interested in it, they may then go on to view sound clashes on YouTube. There’s enough of it up there.

“The profits that are made by these international companies are so vast that they can afford to give money to charities and so on and so forth. This is in many respects, a good thing if they’re taking some of their profits and putting it to the benefit [of reggae].”

Companies are becoming aware of the fact that they cannot be seen to be just taking from the public. They have to be seen to be giving something back. Vast amounts of money were changing hands because artists who want to take part in these clashes are saying, “Well, we’ve got to go through all the trouble of voicing these dubs and staging it.”

This is the other thing I think that people don’t take into account. When you look at the way Red Bull things are staged, each act is responsible for having their own stages constructed. Each stage looks different to the other stage. There’s another aspect of clash culture, which doesn’t exist anymore because everyone plays on the same stage. You don’t even have different sound systems anymore most of the time, because the PA systems in most venues is what it is.

That’s the other thing that’s missing. Mel Cooke, who’s a great journalist in Jamaica, once wrote a fascinating piece about how there was a time when you went to listen to a sound system in Jamaica and you knew you were listening to that sound system because of the way it sounded. More and more now, for practical reasons, sound can’t bring their systems everywhere. If there are three or four selectors playing in one night, they’ll all play off of one sound system. There is a big difference between what’s happening in traditional sound clash culture and what’s happening in Red Bull clash culture. I think there are some dramatic differences. So be it.

Definitely, but in light of what we spoke about earlier, they’re spending so much money on dubs. Some young sound systems feel like they can’t compete because they can’t afford these types of dub. When they go to a Red Bull culture clash, it highlights everything they may not be able to reach.

Yeah, I take your point and I absolutely agree with everything you’ve just said. But, what we have to remember is that the vast majority, 99% or 95% of the people who go to any clash are actually going there as clash fans—not as selectors. In the same way that 25,000 or 30,000 will go to watch a soccer match or a baseball game, but most of them don’t play baseball. They’re going to watch the game. They’re going to watch the cricket match. Of the 25,000 people watching England versus West Indies, all of them love the game of cricket, but just a small percentage actually play it. That applies to clash culture.

I take your point. yes it is disheartening for young selectors to hear sound systems or clash teams playing phenomenal dubs, but of course you’re looking at the high end there. If you look to the clash that we did in Red Bull in 2014, when I was part of Red Bull sound with Chase & Status and Shy FX. remember, they are musicians. I’m not a musician, but Shy FX is a musician. Saul is a musician and Will from Chase & Status. They play instruments and compose music and write and produce songs. They were able to craft rhythms specifically for the night. And it’s inevitable in any business that people who are connected to other people will be able to get things that Joe Public can’t get.

“Let’s imagine if Drake went into the Culture Clash. Drake would be able to get dubs possibly from whoever, top line artists that nobody else could get simply because he’s Drake.”

Wyclef was a good example of this. Back in 2001, Wyclef had a stage show based on playing dubs. I saw him do it. He got big artists to sing dubs. They didn’t understand what they were singing. They didn’t even get their head around what it was. It was just, “Oh, you mean you want a radio drop?” He managed to get those.

It’s inevitable when someone at the high end, in the premier league of the entertainment industry, chooses to come into clash for fun… DJ Khaled, for example, who knows all about clash culture. If he was to go into a clash, he would be able to call upon people who wouldn’t even dream of charging him because they don’t need the money. They’re doing it for fun. Again, there is a big, big difference between that type of clashing and what I would call the foundation style of clashing, the classical form of clashing, which is going back. Let’s trace it back to its origins. Let’s look where it started.

It started in Jamaica, with Duke Reid and King Edwards and Coxsone’s Downbeat, playing songs on white labels that they got from America, and they scratched the label off so no one knew what those songs were. That was how this whole exclusive thing started. In the 1950s, Prince Buster would go to a Duke Reid dance and try and figure out what songs Duke Reid was playing, and go back and inform Coxsone. So that Coxsone dug down, but he could only find those songs in America. No one was making music in Jamaica in the ’50s other than Mento recordings that were very basic.

So, they were flying up to America, working in America or just flying up there, buying rhythm and blues records, boogie woogie records, and bringing them back, scraping the labels off. The “Coxsone Hop,” it wasn’t actually the “Coxsone Hop.” It was “Call of the Gators” by Willis Jackson. But no one knew that for a long time because they just didn’t know who it was by. It was a very different world then. In later years, they would then have sound system clashes where they were making and playing their own music. Because, let’s face it. All those sound systems were making music. They were actually recording music.

They were going to producers before certain songs were released. Those songs were in effect exclusive. Let’s remember where the whole term “dub” came from, because it actually came from recording studios in the United Kingdom and in America. Dubs were copies. What used to happen is at the end of a band’s session in the 1930s, when the session was finished they would say, “Can we have a dub of it?” What they used to do was literally cut an acetate of the recording and that was called a reference disc. It was a copy, and it was cut straight to the acetate. That’s how dubs started.

There’s actually a picture in Jamaica’s Dynamic Studios of Graeme Goodall, the sound engineer, looking at an acetate being cut as a copy of what had happened. That’s what they used to do. Coxsone or Duke Reid would take those acetates and they’d play them that night on their sound system. Historically, we need to remember where this thing started and its significance. Of course, it’s developed into a massive scene now, but I think it’s important that we remember where it began and how it began.

It sounds like thing have changed a lot. Where do you think sound system culture is heading in Jamaica and around the world? Do you think having Red Bull or whoever might be coming in is a good thing? Because they will preserve the culture to a certain extent and you can educate people where this music comes from?

I think if sponsorship means that sound system events can happen, it’s a great thing. But that will never be the governing power of sound system culture because sound system culture is its own generator. It generates its own enthusiasm. It generates its own fan base. It is self-determining and it always has been, because the idea is that people want to hear music. If you take it back to Jamaica, back to the street dances, back to open-air events or club events, you’re looking at the idea of people going out, men dancing in dance troupes, which sometimes is amazing to see what they do, girls in dance troupes, and so on. You’re seeing that dances and dance culture has always been there, Alton Ellis and Eddie Perkins were dancers.

There’s always been an element of dance in our music, in reggae music. It’s always been there. The fact that there have been different dances, the ska, the rock steady, the ride your donkey, the different steps that people have. In later years, this dance or that dance for this season and so on and so forth. Dancing culture is very much a part of sound system culture, very much a part of Jamaican culture, and I think we must always remember that.

“In terms of where the music is going and how it’s developing, nothing remains the same. Everything changes. We have to keep moving forward. We cannot live in the past. We just cannot do that. I don’t live in the past.”

How is that attitude reflected in the way you play live and in your work on the radio?

My radio show, every week, consists of 120 minutes. That’s 30 records I play, 15 in each hour—because I don’t do juggling and all that, I just let a song play for three or three and a half minutes, however long the song is, within reason. Out of that total of 30 records in a two-hour program, I will only play a couple of old records in the second hour in a feature I call “Deep and Heavy,” where I reflect back on the culture. Because if we’re not seen to be breaking new music and pursuing the idea of sharing new music and presenting new music, then our culture is finished and our music is finished.

That’s never going to happen. Our music will always be evolving because there will always be new young people with new ideas. What is a given is the fact that their ideas may not suit you. What I say to people who say, “Music isn’t what it used to be.” Well, of course it isn’t! How could it be? Because it wasn’t what it used to be when you were young, and your parents were telling you they couldn’t stand what you were playing. You have to be mindful of the fact that the world will change and music will keep evolving. If you’re not allowing it to happen you’re being some boring old fart.

Isn’t that what Bob Marley said in his song “Punky Reggae Party”? “No boring old fart will be there.”

I think this is very important. I think we really need to hammer this home: the music is forever changing, and we cannot stand in the way of change. It is unacceptable. We must allow things to evolve. We must encourage new music and new talent. It’s very, very important. If you don’t understand the music and you don’t get it, then it’s not for you. There’s an old saying about surrendering gracefully the things of youth. You know, take kindly the counsel of the years and gracefully surrender the things of youth.

What you as an elder perhaps enjoyed maybe a younger audience don’t enjoy it. They don’t get the pace of it; they don’t like the pace of it. We’re governed now by tempo. We always were, but things are moving faster and faster and faster, and that’s why a lot of the music has changed so much. Therefore, if I can’t identify with the style and tone and delivery of certain new wave Jamaican artists, or artists in general, that’s my prerogative. That doesn’t mean that what they’re doing is of no significance. If it has significance and meaning to an audience of a similar age and understanding, then so be it.

I cannot be all things to all people. No one can. We have to be true to ourselves, and if we’re true to ourselves, we can be true to every man. And I think that’s what we need to be as selectors. I think it would be boring if everyone was to play in the same way. It would be tedious. So the excitement that’s generated by a Tony Matterhorn performance is going to be different to the excitement generated by Mighty Crown. Mighty Crown are incredibly good at being super confident about what they’re going to do.

Right.

And not being frightened to step boldly out, speaking in Jamaican patois, and coming up with good ideas for dubs.

What about Tony?

Equally someone like Fire Links, who is a relatively young selector. He’s been around a while now, but he had this tremendous energy that young people identify with. I’m not so up to speed on the younger selectors in Jamaica because I’m just not. I’m more aware of the foundation sound systems whom I revere because they’ve done so much for the industry.

Let’s talk some more about the Soundclash on the Sea before we wrap up. We don’t know who the winners of the World Clash will be, so we don’t know who that sound system will be. But you’re going to be competing with Tony Matterhorn and Mighty Crown for sure. Do any of those two selectors worry you? Do you have a strategy?

Worry me? No. They don’t worry me because worrying turns a small thing into a big dark shadow. This is just music, this is not rocket science. We’re not putting someone on the moon here. We’re just playing records. I’m not remotely worried by any of my competitors and I never have been.

Any comments for your competitors?

What’s the point of worrying? All I can say is they will come and play a strong game. I wouldn’t expect them to do anything less. I will do my best to play a strong game on the night and to entertain the audience. As I said at the beginning of our conversation, who ultimately wins on the night can be governed by a number of factors. What you have to ask yourself is how did you perform throughout the course of the two or three or four hour set? What did you bring to it that made your contribution unique? That’s what counts. If you don’t turn up you can’t play. You’ve got to be in it to win it, but the winning is not everything. Never was, never will be.

How do you think the other selectors are feeling about playing against you?

“I don’t care. I’ve got no interest in what they’re feeling or whether they care because they’re all mates. They’re all mates of mine. I’ve known these people for years.”

When I say I’m not worried what they think, I’m not worried because I know that they will come with some great ideas. No one knows how it’s going to roll out on the night, but what I do know is the audience who are on that cruise will be entertained. That’s what I’m there to do. That’s what we’re all there to do. If we don’t entertain them, we haven’t done our job. That’s it.

I bumped into Master Simon recently at an event and he said “Rodigan is going to be a pain.” I guess there’s a friendly competition thing going on here. As you say if everybody takes it as fun that will make it great.

Mighty Crown have always commanded the highest respect from me and I don’t give out respect easily. Why should I? People have to earn respect. Mighty Crown have earned the respect not just of me but of legions of fans worldwide and of Jamaicans because of their determination, their commitment, their loyalty to the music. They’ve never jettisoned it. They have maintained a very high standard as selectors. They have a great vintage dub box that they play back in Japan more than they do here. I’ve played with them in Japan. I know their worth and I know and understand and respect their passion. We’ve become good friends across the years because I see in them an undiluted passion and commitment similar to mine, and similar to others who started out as youngsters and progressed.

How long have you known Mighty Crown?

I remember when I first clashed with them they’d just become world champions. That was a number of years ago. I can’t even remember how long ago—1999 or something. Almost 20 years ago. They’d already been going a while before then, but people weren’t aware of them outside of Japan.

This is what we’ve got to remember: that sound system culture is universal. We’ve got sound systems in India and I’m sure we’ll soon have them coming out of China. We’ve certainly got them coming out of the whole of North America and of course South America now. There’s a big reggae scene in South America —in Brazil and so on and so forth. And of course in central Europe. This is a massive scene and we must never forget that.

Brilliant. You said earlier that you’ve even seen Mighty Crown not win a clash. You’ve made a very valid point. It really depends on so many factors: the audience, the opponent who you’re clashing. How do you cope? What do you tell yourself to do on the night so that you can adjust as needed?

To be free. To keep your mind open and to keep your options open.

“Don’t get tied down, don’t get bogged down. It’s like walking in treacle. If you stick to something and you won’t leave it, you won’t move from it, and it can suck you under.”

You’ve got to be fluid. You’ve got to have an open mind. You’ve got to roll with the punches and you’re going to get some punches. Some of them are going to nearly put you down, but you’ve got to come back in again and box. It’s a musical boxing game—that’s what goes on. You’ve got to come fit in terms of having music and ideas.

You’ve got to have some kind of game plan but you’ve got to be open to change. Sound systems will take aim at you, particularly if you draw last, which is always a difficult spot to play. If you’re playing fourth, that means that three other competitors have the opportunity to play, especially if they’ve copied your dub box or they’ve got the same dubs as you. This used to happen in the early days. They’d know Rodigan’s got this dub or that dub and they would try and play them all before you come out. That makes it very difficult for the person who’s playing fourth. Very difficult indeed. That’s another thing that can be hard on the night.

What I do is I try to keep it loose. A sound clash crowd can be very, very fickle. You can be winning the first two or three rounds and getting the biggest forwards and then in the fourth round it can all go horribly wrong and you don’t know why. I think in the 2012 World Clash I was something like four nil down or something against Bass Odyssey. I might have even been five nil down. It just looked pretty damn grim for me and I pulled back. You just don’t know. In the one for one, I was three down, four down. I said “It’s getting sticky for me.” That’s an understatement. I pulled back and I ended up winning. You just don’t know how it will roll out on the night.

The audience can be very fickle. I’ve seen it in Jamaica. We did a big clash. I remember Mighty Crown won virtually every round. The audience were rooting for them. Right at the end the Jamaican audience on their home turf suddenly turned against Mighty Crown and voted in favor of whoever it was. Was it Tony Matterhorn or Bodyguard? I can’t remember who it was, but the point is that can happen. You can see victory in sight and it’s yours for the losing and suddenly you lose it and you can’t even explain why.

Famously that year in 2008 when I said “Oh well I want it to be fair so let’s go for a recount” and that cost me the class. Everyone said “Why did you do that? If you’d stuck with the original judgment that you’d have won the clash.” But hey, I look back on that and I’m not bothered by the fact that I did that. Because I wanted it to be more than apparent that winning was not the most important thing. For me, winning is how was I perceived to be playing. I think that is really important. I think we all have a responsibility to remember where we are, who we are, what we’re doing, and why we’re there.

“I don’t want to get too philosophical about it because primarily it’s music and it’s about having fun, but this is a great majestic music. It has a tremendous wealth and tremendous strength of character. That’s why I’ve always revered this music.”

You obviously take a lot of pride in what you do. In any genre of music to get through as many years as you’ve got through, I’m sure you come across controversy or issues. You mentioned earlier the analogy of just having to “roll with the punches” and keep your mind free during a musical clash. Is that something you’ve also done in real life with your career?

Yes, there will always be haters. There will always be trolls. The internet is a wonderful place to find specific knowledge and information. It’s also a wonderful place for people to hide who they are and say whatever they want to say. Twitter is a place where people can make other peoples’ lives a living hell by obnoxious and vile comments. It’s astonishing to think that people like this actually exist in the world, but they do.

“For every person who thinks you’re a really nice guy there’ll be an number of people that think you are a punk. Or they don’t like you because of your color or because of your success.”

People are often envious of other people just because they’re successful. For no other reason than that. Because they’ve done something with their lives and the other person feels that they should be where that person is. That’s a terrible thing. Bob Andy famously said “We should see the success of everybody else as our own and wish to walk in their footsteps.” I remember Bob Andy saying that of me. We should see it as an opportunity to pursue something when we see other people doing well. I also think when we are doing well ourselves we have a duty to extend a helping hand to enable other people to do well.

Jack Lemmon famously said “when you get to the top remember to send the elevator back down because there’s somebody on the ground floor who’d like to come up.” I always try to send the elevator back down. I always try to help people. I think that no matter what you do in life you are going to be judged by your actions and it is what you leave behind you that people will remember. If you live good with people, if your heart is good, people pick this up. If you’re bad mind and grudgeful, your life will become a misery. Something I learnt many years ago and I wrote down: “There are those who keep themselves in peace and keep peace also with others. There are those who neither have peace nor suffer others to have peace. They are troublesome to others but always more troublesome to themselves.”

There are people in this world who can make our lives very very difficult. You may think you’re popular but there are always going to be people who will object to your popularity and find fault with what you do. But you must ignore them and more important than anything else—and I’ll close on this, you must always, always forgive them. Always forgive people who hate you. Always. Because if you don’t your life will become a living hell.

Amazing.

You have to forgive them.

Follow @Reshma B on Twitter

Follow @RGAT on IG

Subscribe to Boomshots TV

Follow Boomshots on Tumblr

Follow @Boomshots

Leave a Reply