Classic reggae album sees reissue, featuring early work of Carlton Hines

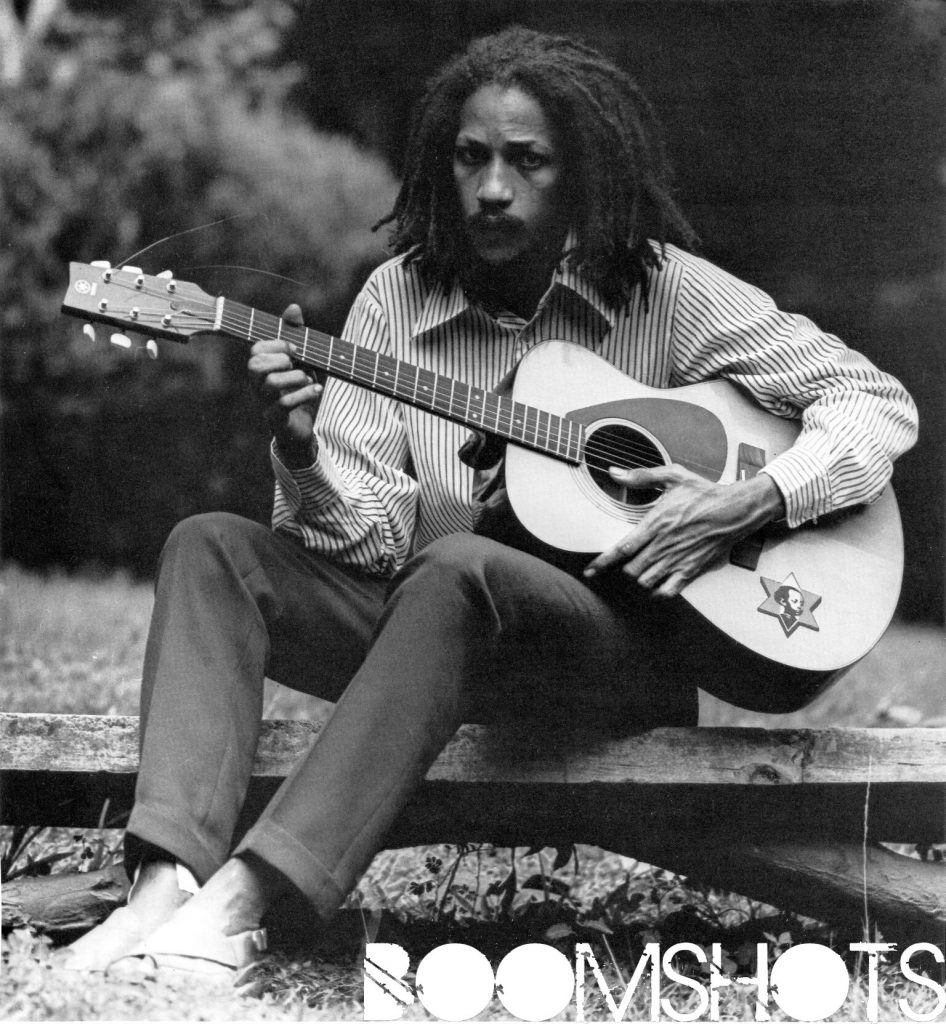

Forty years have provided more than enough perspective to confirm the name Augustus Pablo as a standard bearer in the world of dub reggae. With a catalog of over 40 albums and 200 singles, Pablo rates among the great artist-producers (musicians who ran their own recording sessions versus being strictly financiers or executives). Despite his stature, Pablo was not a prolific producer of full-length vocal LPs, so his handful of efforts in that format are significant. His Hugh Mundell album Africa Must Be Free By 1983 has rightly achieved iconic status among reggae LPs. Tetrack’s lesser-known Let’s Get Started, recorded at the same time with many of the same musicians, matches Africa Must Be Free By 1983 artistically and arguably surpasses Mundell’s album in terms of the songwriting. This is due largely to the contributions of Carlton Hines, whose later writing credits would include Gregory Isaacs’ “Rumours.” Story Continues After The Jump…

The original Let’s Get Started saw limited release on Pablo’s Message label in Jamaica in 1978. This summer, 40 years later, it was reissued on vinyl and CD by Greensleeves Records, along with the closely related dub LP, Eastman Dub.

When the line-up solidified in the mid-70s, Tetrack comprised Paul Mangaroo, Dave Harvey, and Carlton Hines. Hines and Harvey were neighbors in the East Kingston/Mountain View neighborhood of St. Andrew, aspiring singers and ardent followers of area sound systems. Hines recalled the formation of the group and their time with Pablo during a 2008 interview on WKCR-FM in New York. “The name Tetrack …‘Tetrach’ was actually a sound, a sound system that was across the street from where Dave lived: Tetrach Hi-Fi. Owen Archer, he was the owner of Tetrack, and Tetrach was just a killer set. To this day I have heard songs on Tetrach Hi-Fi that I have never heard anywhere else.

“I remember distinctly when we decided to put the group together, Dave Harvey and myself, we used to live like literally next door, [and] Manga (Paul Mangaroo) used to live up the road. One day me and Dave were singing some songs, and we say, ‘we need another man,’ and him say, ‘Manga can sing.’ We just went up the road, knock on Manga’s gate, [and] we a say ‘Manga, we waan form a group,’ and he say ‘yeah?’ Paul is never wearing a shirt, and he went back inside, put on his shirt, and that was the beginning of Tetrack.”

Hines recalled that the group’s path to record for Augustus Pablo came at the behest of a mutual friend. “We met Pablo through Denzel Goodin, a schoolmate of mine and a schoolmate of Pablo’s. So we used to rehearse in this yard in Vineyard Town after school we just hang out and rehearse. We sing everything, everything with a harmony, we sang it – Spinners, Chi-Lites, The Heptones, Paragons, everything. So he would pass through from time to time and he’d say ‘hey, you guys need to go to the studio.’

The group’s initial work with Pablo involved an adaptation of Johnny & The Attractions’ obscure rocksteady masterpiece “Let’s Get Together” and also the creation of lyrics and a melody for a raw Pablo instrumental track. The latter result, “I’m No Satisfied,” would be the group’s first single, but not one included on the full LP.

“We got a little cassette tape, we did acapella, a song called ‘Born To Love You’ [originally by Slim Smith & the Uniques],” recalls Hines. “We did a Heptones version of a Smokey Robinson song and another song called ‘Never Had It So Good’ which is a Chi-Lites song. We went by Pablo, and Pablo is there with his legs crossed as usual, by the ankles, just cooling out… We timidly gave Pablo the cassette, Pablo listen to it and say, ‘the man them busy?’ and we say ‘no man.’ Him say ‘Alright, come with me,’ and we just jump in the car and we went to Black Ants Lane, [which is] literally a lane, unpaved off Red Hills Road, it’s like an uptown ghetto.

“Pablo starts to go through [a] box. Now, he gave us ‘Let’s Get Together’ to learn, and he gave me the riddim [for] ‘I’m Not unSatisfied.’ … We were there, nuff vibes and irie. When ‘Let’s Get Together’ came out, the flip side [dub] was titled ‘Black Ants Lane.’ It was such a natural thing, because that was the foundation of our connection with Pablo.

The songs on Let’s Get Started are notable for the division of lead and harmony vocals among the three singers and, in some cases, within individual songs. “We really wanted to have a sound that was different,” explained Hines. “We felt that it would be good for the group to switch it up.”

Initially, Paul Mangaroo handled the trio’s lead vocals, but “Only Jah Jah Know,” one of the album’s most Afrocentric tracks, would be Carlton Hines’ first crack at taking a lead vocal in addition to the usual songwriting. “We were at Pablo’s place, people like [engineer] Philip Smart used to be around, and we’re rehearsing the song and the song could never come together, and Pablo start to get miserable … and would sometimes take a break and sip a cup [smoke a ganja chalice]. We come back to it again and Pablo a say ‘Yo Carlton wha the man a deal with star? A Jah works enuh, you must sing this song! Wah the man a deal wid star? Just sing the song!’ But I wasn’t a person who normally sing lead. This is the first song I ever did lead on and this was because of Pablo… because I am very comfortable just singing harmony and writing songs.”

Hines recalled the sociocultural climate of Jamaica in the late ’70s as directly influencing the lyrics of “Only Jah Jah Know.” “That song is a result of two basic things. It has to do with my personal philosophy, interests, love, and understanding of black culture, African history and so on—very near and dear to my heart. The song was very reflective of the time period. The music had shifted definitely from straight up lovers thing that you would get to what we would call conscious music, roots and culture. It was a very revolutionary period in Jamaica, because the Rasta thing used to get a whole heap of fight from early on, but it came front and center because what happened is that uptown youth started [to] become Rasta. It wasn’t just an inner city working class thing. You have the rise of the Twelve Tribes Of Israel organization and so forth.”

Other standout tracks on the album include the single “Isn’t It Time” and “Look Within Yourself,” but the entire LP plays as a cohesive whole from top to bottom. Despite the artistic quality of the work, due to its limited distribution on Pablo’s Message label, it has been known up to now principally by deep reggae vinyl collectors and hardcore Augustus Pablo fans, many of whom find the album through an initial discovery of Eastman Dub.

After the recording and release of Let’s Get Started, the group saw the release of a 12-inch single “Love And Unity” on Pablo’s Rockers International label. Then they recorded a handful of independently produced tracks, including the stellar 12-inch “Same Thing Everyday” on Mandingo Hot Stepper. A full LP for Gussie Clarke, Trouble, followed in 1983.

Carlton Hines’ writing credits of at least 75 songs span his years from Tetrack to the present. He wrote an underground roots masterpiece for Dennis Brown called “Deceiving Girl,” one of his personal favorite works. “When I heard D. Brown singing the song, it was indescribable,” he recalls with intense pride.

During a late ’80s stint with producer Gussie Clarke, Hines wrote “Private Beach Party” for Gregory Isaacs, and then followed with the Isaacs megahit “Rumours,” the massive counteraction “Telephone Love” by J.C. Lodge and the deejay version “Nuff Respect” by Lady G, a triple play of dancehall anthems, each of them key songs in the story of Jamaican music.

Hines moved the US in 1987 and became a social studies teacher. He used songs such as the Abyssinians’ “Declaration of Rights,” Bob Marley’s “Zimbabwe,” and Tetrack’s “Only Jah Jah Know” to illustrate social activism in songwriting.

While Hines’ legacy as a songwriter and performer hasn’t brought him great notoriety, the artistic quality and relevance of his work from the roots reggae era into the dancehall era ensures him a place within the broader story of Jamaican popular music.

Leave a Reply