The Grammy-Nominated Jamaican Jazz Master Nices Up The Blue Note

With 50 years of making music and some 70 records under his belt, the Jamaican-born and world-renowned pianist Monty Alexander has finally received his first Grammy nomination. His live album Harlem-Kingston Express got the nod for the Best Reggae Album this year. Alexander is considered a first-rate pianist in international jazz circles, yet he got his start sitting in with mento bands on accordion, or recording for Coxsone Dodd and Randy Chin. He went on to play with Dizzy Gillespie, record with Quincy Jones, and accompany Frank Sinatra when he passed through Jilly’s on West 52nd Street. In other words—Monty bust big a farin’. Yet instead of turning his back on the Jamaican music that shaped him, he took it back to the foundation and found ways to blend the two with one sound coming through pure and true. That’s just what Monty has been doing during his two-week residency at NYC’s Blue Note, inviting 50 years’ worth of friends from the worlds of jazz and reggae to jam side by side, giving his lucky listeners “The Full Monty.”

Boomshots caught up with Monty just before his stand at the Blue Note to reason about reggae, jazz, and the universal beat. But first check out this video interview shot when he passed through our Strictly Boomshots show on RadioLily.com between sets on his first night at the Blue Note. Later that night he would be joined by surprise guest Kevin Spacey, who jumped onstage to perform Sinatra’s “Come Fly With Me.” There’s never a dull moment when Monty’s in the house.

How did you learn that you had been nominated for a Grammy?

Just a simple email that came through about six weeks or two months ago. I can’t remember exactly.

Was it an official Grammy communiqué or a friend of yours, like Hey…?

I think the Grammy communiqué. And then not long after that, a couple of people I know who were loving their music. And the record company, the independent company I made that CD with, saying they were really excited. Because they were glad to make the record, but they had no idea that it would be received so well by DJs out there—the Jazz Policy as well as another chart called Jazz Week World Chart.

And I had had a recording that was released on another small independent label, which was a straight-ahead jazz kind of record. Live concerts in Europe…. Mind you Rob, this is my 70th CD. Seventy.

Seven Zero.

Seven Zero. I mean, from the first time I made a record in Jamaica when I was like 14, 15 years old—back in 59 or something like that.

Well now that you’ve mentioned it you have to say what that record was.

Well I had a little band in school and I made some recordings and they ended up on… Cause I can talk to you like I know you’re a deep devotee of Jamaican music as well.

I am, yes I am as a matter of fact.

Dave Rodney told me. But it blows my mind when I think back that I used to play on early sessions for recording artists ten years before Bob Marley came along actually—when I think about it. But these records, I had a band and we come up with a little name called Monty and the Cyclones. And under that name I made a few tracks for the old Federal label—Ken Khouri, that whole thing. And then I ended up, some of the things I ended up doing for Coxsone Dodd, who I used to play on records with. So that’s going way back, but it wasn’t even a CD, it was a 45—double-sided things. And they came out, they had what was called the Hit Parade, the Jamaican Hit Parade. This was the early times.

So let’s get back to the latest album, that was nominated for a Grammy.

Thata album he jazz guys and the reggae rhythm guys. I put it together, and it’s my imaginary musical train called Harlem-Kingston Express.

It was done live at a club in New York called Dizzy’s—at Jazz at Lincoln Center. So the lady with a label called Motema picked up the CD and released it. And right on the heels of this other album called Uplift, which stayed on the chart for like 3 weeks at #1.

This other one now—the same DJs who are pure jazz jazz kind of people, and they know I’m Monty the Jamaican, they picked this up and two thirds of the record is definite roots. They picked it up and it stayed on the chart for 14 weeks at #1. Now that’s a kind of an interesting development.

It is an interesting development. That’s major recognition for reggae music.

Not only for me, but for the fact of this thing that I always believed in: Good music is good music. And the fact that they knew my name—being the jazz guy coming along with my Jamaican side—the door was open and they just kept playing it, playing it, playing it, playing it. And it was… Wow, what an interesting development.

Yes it is. And speaking about that connection, it reminds me of something Ernest Ranglin told me. While he was doing serious jazz music with different international people, he would also do the local reggae recordings but he wouldn’t use his name on those records. How did you bridge the gap between those two worlds of jazz and reggae?

That’s a very very interesting question and of course Ernie is a different person and I know him, by the way, from I was 12 years old. Ernie, God, we go way back, and we made a whole lot of records together and what have you. And we’re two different people so his reaction to that is because of certain impressions he had. But whereas with me now—I don’t know if this directly answers your question—I come to America and immediately I’m trying to fit in and get in with the great jazz musicians in America. You know, New York—I came in the early 60s.

As I went along, in the early days of that, when people would say, “Where you from?” I would say “Jamaica” and they all thought I meant Jamaica, Long Island. The point being, this was before Desmond Dekker and “The Israelites.” About the same time as Desmond Dekker and “The Israelites,” and then here come Harder They Come. And little by little…

But they accepted me apparently because of my musicianship. Not because of anything else. But as the years went by, I just felt such a great “Come Home” feeling to my life growing up in Jamaica until I was 17 years old. All I experienced as a kid growing up, as a school boy there, as a musician hanging out with all these great guys from Don Drummond right to Ernie Ranglin to everybody.

And then I felt, you know what? I feel a little estranged from the latest crop of “jazz experts” let’s call it. Because they’re coming with this intellectual jazz—and how fabulous it is, no question, I love it. But I come from the old school brothers who play jazz but it was swinging—you know what I mean?

When I met Coxsone Dodd he said “Me’s a jazz man.”

There you go, and in fact so is Chris Blackwell. Blackwell used to come to New York and go to the Village Vanguarde to hear Miles Davis. Even in the early days, before Bob Marley. So jazz was really how…. And by the way, Coxsone and Roland Alphonso were like buddies I think from even school. They went to school together.

Oh really?

Yes. But they were really jazz men. And all Coxsone did is just say listen, “Keep the beat, keep the beat.” And then the drummer would have to play the beat. And needless to say Jamaicans turned the beat around and made it what it was and it had its own true unique personality. And everybody was thinking Louis Jordan and New Orleans and you know… but from a jazz perspective. Yes.

Right, right. There’s a whole book to be written about that.

Oh yeah, it’s funny. Cause even though I’m a musician first and foremost, I’ve been an observer of this social experience. You know, how it happened. And then, you know, Bob Marley came with his powerful way of doing things, and here we are. But I still love my mento from the old-time days, you know? And then transitioning into the blues with the Skatalites… Because I played with those guys before they called themselves the Skatalites. I played on a few tracks, some records—you know.

Okay, a few, right?

But like Ernie, you kinda thinking, “Well if they think I’m a jazz guy, then maybe the roots people…” And vice-versa, the roots people might be thinking… But I found out, and here’s what I found out—the tremendous value and appreciation that each side has for the other when you come pure and true with what you have to say.

And that’s what Ranglin is about. Ranglin starts playing the guitar, and every note he play is him. And I like to say that’s me too. When I play, it’s me. I’m not trying to be anybody but me.

That’s real talk. Now back to this Grammy nomination, this isn’t your first nomination is it?

It is indeed my first Grammy nomination.

Oh it is your first—my goodness!

First time. Yessir.

With all those 70 records under my belt.

With all them 70 records under my belt. I just keep moving. I don’t know. The little labels I was with. But I was with some decent ones. Still nobody was pushing the product or getting it out there like it coulda shoulda woulda. When I was with a company called TelArc—a decent midrange label that’s now part of Concorde—I made these two albums that were interpretations of Bob’s music. And they were received quite well and, you know, lovely lovely thing. But they never did anything to stick ’em out there.

It’s sorta like “whoever finds it finds it.”

Yeah, exactly. And I tried to convince them how to market it in the third-world arena for Jamaican fans, but they didn’t quite get it. You know? Now if I was linked up with VP Records or somebody, maybe I woulda been in the reggae category.

So I bring this slightly confused persona—just like Ernie. We’re jazz people but we’re still connected to the roots. You know?

You are that connection. Now let’s talk about this residency at the Blue Note, cause that’s the perfect segue.

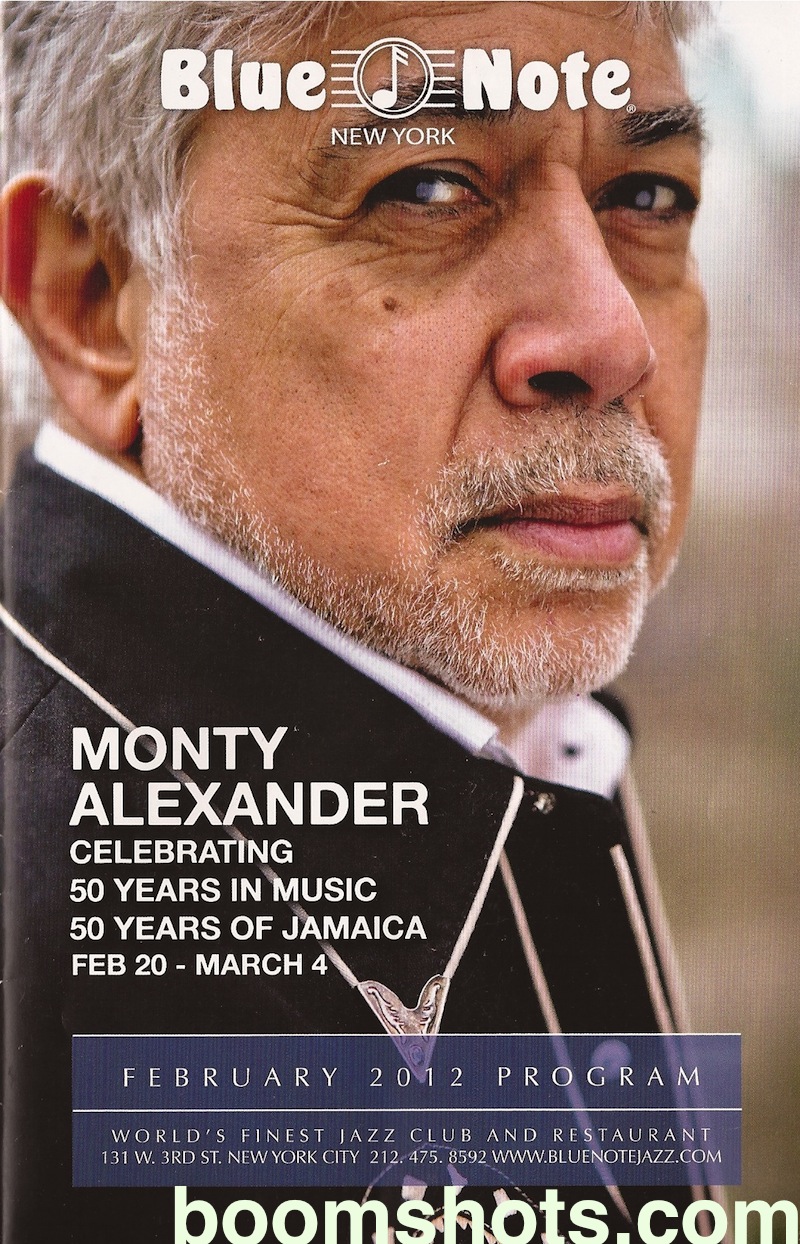

Thank you very much. So that came about as another one of my friends who said, “Monty you realize this is 50 years you’ve been doing music…” And next thing it get out there as a little publicity thing—50 years coinciding with Jamaica’s 50 years. The irony of it all…

So among other things I did, besides these two recordings, I went to the people at the Blue Note, where I actually played in their first year, 30 years ago when they started. So they know me that well. I always came there with my jazz things, but also kinda leanin’ towards my Jamaican experience. But anyhow I said “Listen I’d like to do this program where I come in and ask all my friends to come in for an evening. For example, on one night I’ll have musicians like… always people I played with, not just calling up people and asking them to come. But the second week of the booking I want to bring my native rhythm and roots. And the people there said “Yeah! Absolutely.”

That’s so cool.

The Blue Note is connected to B.B. Kings, and they are often presenting some of the top reggae artists. But they never thought that they would have the chance to bring it down there. Cause there was nobody who was connected like I am.

So I called my friends Sly & Robbie and Ernie Ranglin, who we just toured Japan with two months before that. And that’s why we’re gonna do Europe this year. They’re gonna call it Jamaican Legends and that’s gonna be a quartet—Ranglin, me, Sly & Robbie.

Wow. Are you serious?

That’s really true. Isn’t that wonderful, man?

And one would hope that there will be some recordings from that quartet.

Well indeed, that is what we should have been doing. But while we’re at the Blue Note we may record. And so what I mean in the second week Sly & Robbie are coming. Ernie couldn’t be on those, but he will be with me when we do the opening night. I call it Harlem-Kingston Express, featuring special guest Ernie Ranglin. And then after that night, Tuesday right till the next Tuesday, I have all these different great people I’ve played with. I do a night dedicated to my time at Jilly Rizzo’s club Jilly’s. I literally played for Mr. Sinatra back then. And that’s when I first met Quincy Jones. And I understand you used to be at VIBE.

Yes Quincy kept my family fed for many years.

Well I tell you, when I was playing at the Playboy Club I met him back in 65 or 1966. And he had me playing on some of his records. I played on a couple of movie soundtracks. And I played on the Bill Cosby Show—one of his earlier shows. But I’ve seen Q all through the years… a nice vibe.

Yeah, that’s one of the real big men in the business.

And I’m still trying to explain reggae to him. [Laughs.]

You know I’m glad you mentioned that, cause I tried just a little bit myself.

Look—when you grow up deep in the hood, and what R&B is, and jazz is, and all— it’s really hard, unless you have a life experience. to turn it around. You know, like the right woman or something like that. [Laughs.]

So all he needs is the right woman?

The right woman or the right smoke or the right this or the right that. [Laughs.]

But it never really happened. I know he went down and visited Chris Blackwell. And I know he likes reggae, but his kids—you know, his various children—they love it.

I had this conversation with him and he said “Americans can’t get with that beat. And it’s gotta be on the two and the four.”

You said exactly what he said to me. Exactly. And I’m that familiar with him where it almost turned into a small argument.

And he also said “When Stevie did it, he had to change it to the two and the four.”

Yeah but along with that, he apparently literally asked Bob Marley, who had the frustration—the same way Jimi Hendrix did, because Jimi Hendrix never had black people listening to his music either. And he brought that up, and it was something missing. And it all came down to nobody brought it to them in the right way. And it’s now happening. It’s beginning to happen, where when Americans are exposed to it in a certain way, they will be instantly take right down to the roots. I see it. I feel it. It’s happening. You know? And the influence and the inspiration behind all the hip-hop artists and the popular people, a lot of them I believe are trying to bring that into what they are doing.

Wait—so you’re saying Q spoke with Bob about this.

Yep he actually had an occasion where he was talking to him and he lamented the fact where more black Americans weren’t digging his music.

And Q probably gave Bob that same “two and the four” conversation.

[Laughs] Exactly. And I’m trying to express to him how we leave the one open. You feel the one, and the two is where we lead onto the groove. You know? It’s simple as that. That’s all there is to it. It’s what happen when you mix up New Orleans, and you put the clave beat, and it takes on the personality of the way Jamaicans talk, walk, eat… and then it takes on its own form. Because that clave beat that comes from Africa, you hear it in Brazil, you hear it in Puerto Rico, you hear it in Haiti. But Jamaicans, somehow when they got ahold of it, they took it to the deepest groove you could find.

And even though it is a worldwide beat and it’s an African thing, it seems like the style that the world imitates is the Jamaican form of it.

Well that’s without question. And that’s what I grew up with, all up inside my bones. But no less than when I first heard Ray Charles, because I was loving American rhythm & blues. Same way Coxsone heard R&B. So when I play, like Ernie, we’ve all got this big old gumbo to pick from. You know? But I think the deepest part of the root is the old-school Jamaican folk music that we call mento. And if you talk to Sly Dunbar, he’ll tell you the same thing.

So you know these guys, The Jolly Boys?

Oh yeah, I know the Jolly Boys. They are one of so many of those kinds of bands—actually very few of them surviving today. And Jolly Boys had that little extra boost to have a commercial recording that people know about them. But there were so many of those mento bands earlier on as I was growing up. I had an accordion as a kid and I couldn’t help myself, I had to go play with every band and sit in with Lord Power and Count Lasher and all these guys singing the old rude calypsos. I was a kid, I was 8 years old doing that.

With that bass box…

The rumba box.

Now you mention the accordion, and of course Augustus Pablo had his melodica…

Which I use a lot too.

And where did you access a piano?

Well in Jamaica, people had pianos in their homes and in the recording studio. Federal had an old upright that barely sounded decent, but it still worked. You know? So pianos were ther. The pianos were in the hotels where the tourists came.

But the musicians who didn’t have the good fortune to own a piano but they wanted to make up a song, they found a way. Like Augustus Pablo’s melodica, somebody must have given him one or he found one—because it’s an inexpensive piece of plastic. But people who are coming from the roots and the soul, they take very little and make a lot out of it. And that’s what Augustus Pablo and King Tubby and all those guys did. And it’s the same with the steel drum in Trinidad. Steel drum was just something that the oil companies left lying around. And you give that to some creative people, poor people, and they don’t know where to turn, they’ve got to go find a way to make it useful and make beautiful music out of that thing. Yeah, you take the side of the pig that nobody wanna eat and make the tastiest jerk pork.

And what about you, how did you learn?

Well I had a piano at home. I was 3, 4 years old, picking out songs, having fun like a kid. And then before you know it, I’m playing rhythm and people dancing and I got my confidence going from a very early age. And entertaining the neighbors, and I took piano lessons but I would tell myself I didn’t want no more lessons cause I didn’t like the teacher slapping me on my knuckles.

Somehow I picked up the language, apparently, good enough where I played with Dizzy Gillespie and Ray Brown and Milt Jackson and Quincy Jones and all these people. And somewhat like Ernie, keeping my Jamaican part secret.

By all means necessary.

By any means, by all means.

Yeah but “by any means” you could pick this one or that one—but I say “by all means.” Cause we take all of them.

I love it. So I had a piano. My father had a reasonable income and next thing you know he give me the accordion. And my hero was Louis Armstrong. I saw Louis Armstrong on stage in Jamaica—he was my biggest hero. The next day I begged my father for a trumpet so I had a trumpet but I couldn’t play it. So I gave up the trumpet.

Leave that to Dizzy.

Leave it to Quincy. He was a great trumpet player, by the way.

I hear Tubby was a big jazz collector too.

Not surprised. Not surprised. A lot of those guys were tuned in to what was coming from the States. Back in the 50s, we had a local promoter down there. The father of a very big man in the media named Steven Hill. And Steven Hill Sr., he was the one bringing Armstrong. He brought Nat King Cole—my other hero, who I also saw—he brought pop bands. He would bring Brook Benton and Jackie Wilson. So I saw all these people, along with local musicians and mento music. This was in the 50s. So music coming from all sides in Jamaica, you know, it took the shape that it did.

I remember Johnny Nash coming to Jamaica. That’s how it got out of Jamaica the first time, I believe.

So that predates Desmond Dekker?

Absolutely. He was a savvy guy and he had a couple of hits in the U.S. and I think he might have fallen in love with some lady and wanted to stay in Jamaica. And he made records for Khouri at Federal. And the next thing was “I can see clearly” and “Stir It Up” and a few good Bob songs… I think that’s how it really started.

Yeah people talk about the Scratch sessions, but there was a big learning process that went on between the Wailers and JAD Records.

I feel like I’m talking to a kindred spirit.

We could go on for hours, but let’s bring it back to the Blue Note. Who are some of the guests you are expecting?

Here’s what’s happening—so we’re going to do Monty meets Sly & Robbie. The next night is none other than Shaggy coming, and we’re both nominees. And we did another gig together and I had a good hook-up with him. And I just heard good news that maybe Toots is gonna join me. And the next night I have the wonderful and incredible Miss Diana King and then Tarrus Riley and Dean Frasier. So I’m bringing Jamaica to the Blue Note.

And the fact that I’ve played with all those. You know and then I’ll have Christian McBride and Russell Malone for two nights playing reflections of what I did on Triple Treat with Ray Brown and Herb Ellis.

And then another night I’ll have Black Martino the great jazz guitar player joining me. Then I’ll have Dr. Lonnie Smith, the great Hammond B3 organ player, swinging hard. And then one night I do a tribute to Trinidad and I do the steel drum concept. I made some records in the 70s like that. And then the final night that week is Freddie Cole and Dee-Dee Bridgewater and I’ll remember my time at Jillie’s where Quincy and Sinatra used to come.

Did Frank like reggae?

Frank, I have no idea. All I ever talked to Sinatra about was boxing. [Laughs] I had a couple of times where I would say “Did you see the fight last week with Ali?” And he’d talk because he loved boxing. I didn’t know what else to talk about. But literally man, I played at Jillies. And there were a couple of occasions where he got up and vocalized and I played piano for him.

Wow.

Absolutely. And those days I saw no Jamaicans. I mean, my mother came in the club one time, and another person maybe. But mosty I was so caught up in that world of excitement. The wise guys and the hookers.

All of that.

So I was just adapting like a lot of us coming from another place. You kinda intermingle and next thing you know you’re kinda among the folks, and you keep quiet to your roots and whatever that was about. But Jillie’s was a very important time for me, like I said. Miles Davis used to come in and hang out there and I got to know Miles very well at the time. And he liked reggae. I found out later that he had heard the one-drop. And when he was recuperating from some bad self-infliction—whatever it was—he went to Ocho Rios and I’ve heard the story about how he was there digging reggae music. No question about it.

MONTY ALEXANDER will be rocking The Blue Note tonight with special guests Tarrus Riley and Dean Fraser. And who knows who else might pass through?

Leave a Reply